As a kid, I loved math. I was always a few books ahead of the rest of the class, and in high school, I aced the national exams while prioritizing xbox with my best friend. Numbers are my thing. Tell me your name, and I’ll forget it before I’ve even said mine. Tell me your personal ID number, and I’ll remember it next week.

When I’m good at something, I tend to do something else. In hindsight, that might seem stupid. Building on your natural talent and becoming truly great in a specific niche is exactly what I tell all of you to do when starting a company. Dare to be niche. But I haven’t always practiced what I now preach. Instead, I’ve become somewhat good at many things, but the best at none.

That’s why I chose to study at the Stockholm School of Economics instead of The Royal Institute of Technology - a strange choice, considering my love for math. I wanted to force myself into something less intuitive.

Of course, the course I enjoyed the most at SSE was statistics - the only truly quantitative subject in the entire management program (I didn’t study finance). That was the seed that grew into my fascination with AI.

This long backstory is the reason I ended up in the AI-space early but more on a strategic level rather than hands on with the models. So my interest in AI dates back to 2010, and I’ve been working actively with it since 2016.

I’ve always worked with the more numerical side of AI - predictive AI. A vertical of AI that has progressed without the worst irrational hype and where most of the work still remains to be done. It’s not a one-size-fits-all game like the large language models have become.

The beauty (and beast) of a global model like ChatGPT, which can handle everything linguistic in multiple languages, is how fast it scales. When everyone can and wants to try the same phenomenon simultaneously - things move quickly.

The goldrush of generative AI makes the perfect conditions to breed the biggest and baddest kind of Capitaholics: the blitzscalers.

The blitzscaling strategy - described in a book by Reid Hoffman (yes, he is the founder of Linkedin (the home of 1 billion AI-experts)) - is to become the biggest in a new or disrupted market - the fastest - to outcompete all the competition and create a monopoly. The strategy claims that this makes sense in a market that is a winner-takes-it-all-market (think of Facebook for example). It’s also the perfect strategy for becoming a Capitaholic. Often, this happens at a scale that hurts not only the company but also its investors and employees which is bad enough. A few, of course, succeed and survive - but profitability must eventually appear, valuations must normalize, and along that road, setbacks are inevitable even for those few lucky ones.

In rare cases, the hype becomes so overwhelming that it spreads beyond venture capitalists to infect the entire world to become codependent Capitaholics. That happened in 2000 with the dot-com bubble. It’s happening again now with AI.

Let me outline a few points to support that claim:

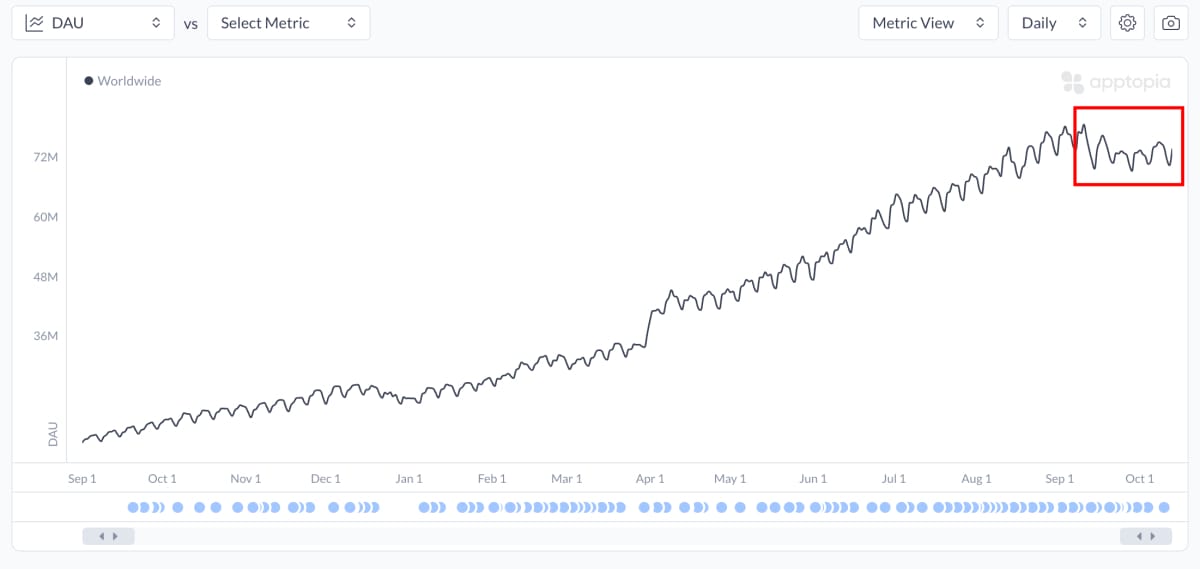

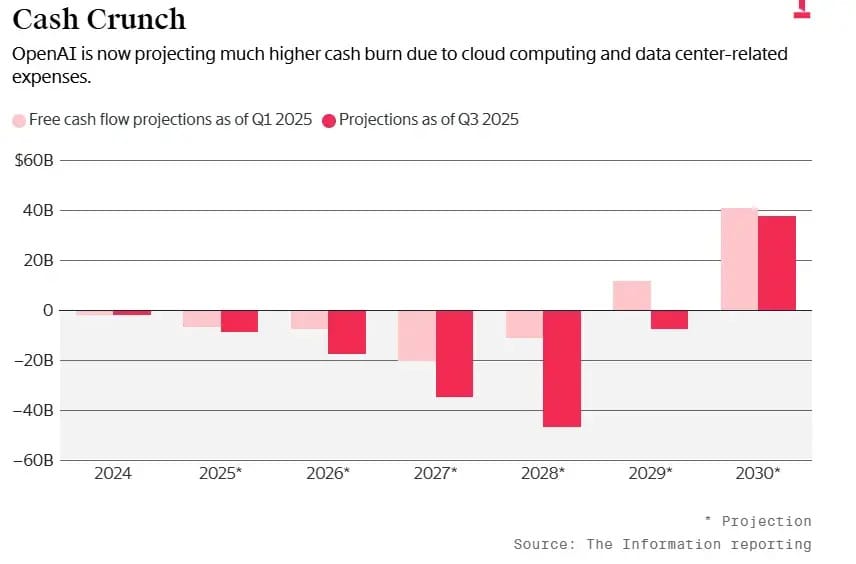

OpenAI lost $11.5 billion last quarter. That’s an insane amount of money though defensible, given the growth. However, much of the investment is amortized forward, meaning their cash flow is likely even worse. There are also signs that usage is flattening. What happens with the valuation if the growth stops or at least looses its pace.

Without data center investments, the U.S. economy would be basically stagnant right now.

Source: FortuneMichael Burry (of The Big Short) — who correctly predicted and shorted the U.S. housing crisis in 2008 — has now shorted Palantir and Nvidia.

On November 5, Deutsche Bank announced they are exploring short positions on AI-related stocks as a hedge against the massive loans they’ve issued to these unprofitable “blitzscalers.” They’re also looking at other mechanisms to distribute risk through complex financial vehicles — meaning that when they spread the risk, they spread it into society.

Source: Financial TimesNvidia predicts that leading AI companies will invest $3–4 trillion in AI chips over the next five years. For context: France’s entire GDP is $3.36 trillion, making it the world’s seventh-largest economy.

Source: Yahoo Finance

These investments must be depreciated fast - the tech evolves quickly, and the best chips lose value quickly.

Normal organic capital from Venture Capital is not enough. Funding rounds have gotten “creative.” According to OpenAI’s projections, they’ll need massive capital inflows in the coming years. The only player who can invest at that scale right now is Nvidia — maybe Apple or one of the other “Magnificent 7,” which, by the way, represent 36% of the S&P 500’s total value. This has laid the foundation for cross-ownership. The easiest way to explain it is with a meme.